Since 2001 William Kentridge has created large tapestries for which individual collages and drawings served as models for the weaving. A selection of tapestries from the Porter Series (2001) will be supplemented in the exhibition at Kewenig with further tapestries, including a motif from the Winterreise (Winter Journey, 2013). To the twenty-four songs from Franz Schubert's Winterreise, William Kentridge has drawn twenty-four animation films that have been shown in co-operation with various theatres recently in Aix-en-Provence, Hanover, Vienna, Amsterdam, New York and Lille. Apart from the tapestries, the exhibition shows a few of the artist's paper works which represent independent works even though they sometimes served as models for the tapestries.

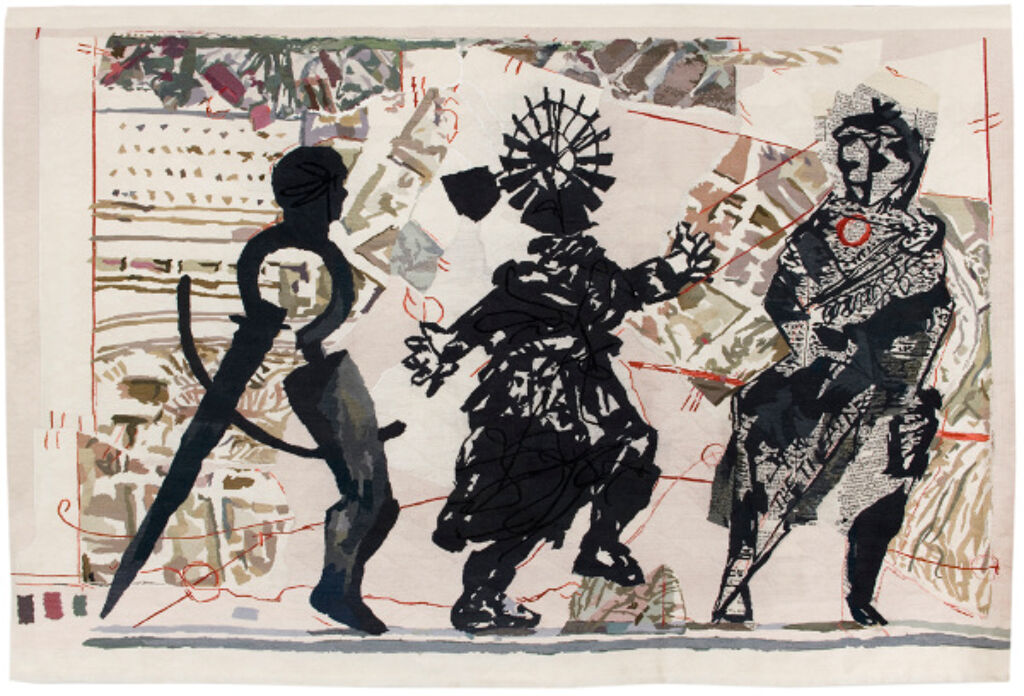

For the collated models oft he tapestries, Kentridge glues fragments of torn paper on maps and book-pages that he takes mainly from antique atlases from the nineteenth century. The figures coming about in this way, for instance, the Porter Series, seem like paper cutouts. They are nomads, refugees or adventurers carrying tools, furniture or instruments, often from colonial times, which blur with the dark silhouettes of their bodies. Kentridge draws over the collages with lines of coloured pastel crayons resembling geological or meteorological fine details - wind movements, water-lines or degrees of latitude - thus putting the figures again into relation with the background indicated in the title toward which they move: the maps of a period of imperialism in which the expansion of European territories was at its greatest.

The Marguerite Stephens Tapestry Studio established in 1963 transforms the multilayered paper works through an elaborate process of handicraft into large tapestries. Located in Diepsloot, a suburb of Johannesburg, Stephens employs a team of local weavers, cotton spinners and dyers who work with vertical looms, processing mohair wool from Swaziland, silk, as well as acrylic and polyester fibres.

In Kentridge's work process, such as tearing paper or the gestural stroke of the crayon, there is not only space for contingency, but also for the special qualities of the material he is using. For instance, by weaving in the striking torn edges of the paper of the model into the formal language of the tapestry, the secondary creative process of weaving catches the material aesthetics of the paper model in the medium of tapestry which, in turn, is inscribed in a centuries-old, intercultural tradition. In the handicraft perfection of the weaving process, that goes back to French weaving techniques of the seventeenth century, the paper works find a complement and an ennoblement.